Women in Journalism

Team Culture Lab

6 October 2017

As a build up to our special screening of Velvet Revolution, we ran a campaign on social media paying homage to women journalists.

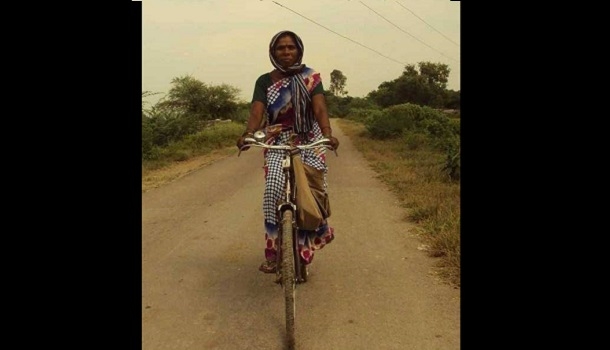

Shivdevi of Khabar Lahariya from Banda, Bundelkhand (image above)

"Just when it seemed that an abusive marriage was all there was to life, I took what I can now call my first life-changing decision: I enrolled myself in a six-month residual course that the Mahila Shikshan Kendra in Chitrakoot was running for Dalit and Adivasi women. My in-laws couldn’t fathom what it meant to be away studying for six months, and told me I shouldn’t ever come back. “Bada DM banegi (As if you’re going to be the District Magistrate)”, was their taunt. But I knew I had to do this. I left my six-month-old with my parents and I went.

Today, six years later, I am not the DM – thankfully! – but I am a well-respected, well-known journalist in Banda. They all know me as Shivdevi from Khabar Lahariya, the journalist on the Scooty!

It has been anything but easy. In the badlands of Bundelkhand, as patriarchal and feudal as it gets, being a Dalit woman reporter has meant knowing and tasting fear. We run into it almost every day, but I remember the first time I felt it.

This was in 2014, when I was reporting on the Lok Sabha elections, and walking from Palauni to Palra – a stretch of land that’s not well-inhabited and also includes a large patch of jungles. I suddenly found myself encircled by a group of men. I recognized them in an instant – they were Thakurs, all of them – here, in Bundelkhand they wear their entitlement on their sleeve. They started interrogating me – who I was, why did I have newspaper copies, what business I had going about asking questions. When I told them I was a reporter, they scoffed and became openly abusive. “Aurat ho, abhi toh jaane de rahe hain, agli baar mat aana yahaan (You’re a woman, so we’re letting you go today, but don’t you dare ever come back here again),” they said. “I am a reporter”, I replied, “If my story is here, I will come here.” My heart was pounding, but somehow I gathered my guts and said that.

As I walked away, I tried not to look back to see if they were following me. It was an eight-kilometre stretch and I was very afraid that someone else would suddenly spring up on me and maybe get violent. But I kept walking. It was late by the time I reached home and only when I sat down, did I realize the gravity of what had just happened. But my own bravado gave me confidence and hope.

Today, I can say it with pride: I feel like I can go anywhere, report on anything, and nobody has the right to intimidate me."

General Narsamma of Sangham Radio

General Narsamma of Sangham Radio

"Mobility is the biggest constraint in villages. In spite of knowing how to drive a two wheeler, I have been bullied on roads - people have told me to stop traveling like a man. I remember when I started recording for the radio, people highly discouraged me, saying it's not something that I am capable of. Finally, there are young boys who constantly create a nuisance during programs on Sangham Radio, especially during the segment where people can call in for song requests. Despite all of these obstacles, I know how important it is for Sangham Radio to exist. Community radios like ours revive the forgotten and lost traditional practices, indigenous knowledge systems and cultures. It has given me a means of livelihood, an identity and recognition for my work."

Rohini Pawar of Video Volunteers

Rohini Pawar of Video Volunteers

"I was brought up in an orthodox family where girls weren’t allowed to venture out of their homes on their own. I was educated till 10th standard and married off at the age of 15. However, I was driven to do something independently that would change our society for good. I joined Video Volunteers in 2010 and I went for their 15-day training session on my own – it was the first time I had ever traveled in a train and the first time I had traveled alone. I couldn’t wait to get back and starting reporting in my own village. It didn’t turn out to be the way I had imagined. My family didn’t support me and I ended up reporting cases from other villages for over a year. I campaigned by myself to allow entry for women in the Mkhaskoba temple at Veer Village without any support from anyone – including the women. I also initiated a protest against the wage gap in the farming community of Walhe village where women labourers were being paid 90 rupees lesser than their male counterparts for the same amount of work. I have received a lot of praise from various civic institutions, but when I started out, nobody approved of my work. People from my community would tell my in-laws to keep a check on me and stop me from protesting. I would even receive messages from random numbers, asking me to avoid going against the authorities. It was difficult for me to stand up for myself under such circumstances, but I was resolute about making things better for other girls in my community so that they don’t face the same issues as I did."

Shikha Kumari Paharin of Video Volunteers

Shikha Kumari Paharin of Video Volunteers

"I belong to the Pahariya community, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group, from Jharkhand's Sahebganj district. I forayed into social work in 2010 and joined Video Volunteers in 2014. As a member of the Pahariya community, I had to struggle a lot to make sure that my voice is heard. The civic authorities perceived us as obnoxious and all our complaints were ignored. When I started reporting, I was advised to stay at home and was told to be mindful of “what happens to girls of my community who aspire to have careers.”

The gravest threat I have faced since I started out as a journalist was when I reported the case of Jharkhand’s Utramit Primary School in 2014. A number of children from my community were enrolled in this school. However, it would always remain shut. The kids had to travel for over six kilometres to reach it but the teachers would be absent, there would be no midday meals, and the funds that were allocated by the state would never ultimately reach the school. When I reported this case, all the teachers who I spoke against formed a union of sorts to threaten me. Most of the threats were indirect, but one teacher warned me that he would bury me alive if I was found in the village again. My friends advised me to relocate and as I was a single mother of two children, I decided it would be unsafe to continue living in that area.

The story had an impact – two years later the teachers were replaced and a new headmaster was appointed, promising to make conditions better. Despite my work being appreciated, I continue to face discrimination and dismissal by civic authorities on the grounds of identity."