RAJYASHRI GOODY ON HER ARTISTIC PRACTICE AND THE CASTE POLITICS OF FOOD

TEAM CULTURE LAB

25 July 2020

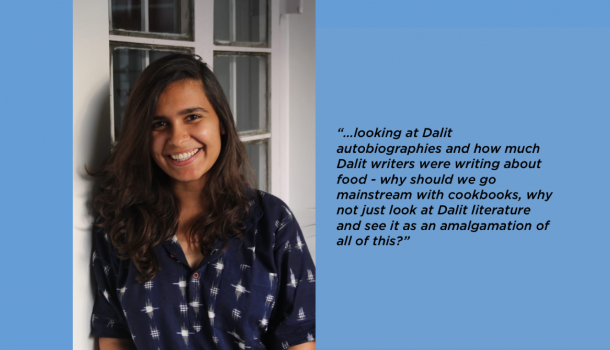

Last week, for the third session of our Leadership Programme masterclass series we hosted artist Rajyashri Goody. Rajyashri is a Visual Artist and Ethnographer who through the use of various mediums, including writing, ceramics, photography, video, and sculptural works made with found objects and food items, attempts to decode and make visible instances of everyday power and resistance within Dalit communities in India. You can read more about her work here.

During her lecture, she spoke to us about the intertwined relationship between caste and food, the exclusion of Dalit food histories from popular discourse, and the ways in which she navigates these with her artistic practice.

Rajyashri began her lecture by speaking about how the way we experience food is also a caste experience. While for upper caste communities food is linked to taste, enjoyment and a celebration of one's culture, for those from marginalized communities, especially Dalit people, memories of food are often linked to hunger, continual deprivation, practices of begging, stealing, eating leftover food or food that is thrown away and feelings of disgust, shame and fear. And these experiences with food have in turn given birth to unique food cultures. For instance, for Dalits who own no land and cannot afford to buy fruits and vegetables, there is no access to seasonal fruits and vegetables and so a lot of Dalit communities depend on foraging as a way of finding natural food resources which form the base of a large part of Dalit cuisine.

Rajyashri spoke about a dish she remembers eating as a child called Ukadala which was a mixture of leftover food mixed together in a single utensil and eaten. It was only later that she realized that the creation of Ukadala emerged from the time when Dalit people would beg for food and owning only one utensil, would mix all the food they would get and eat it from a single utensil as opposed to using separate utensils for separate dishes. This culture of deprivation she pointed out also had long term consequences -an instance of which is how people from her community, the Mahars, suffered from a particular kind of anaemia caused by eating the meat of dead rats, the only kind of meat which was accessible to them. The control of access and affordability to food thus was a very active way of maintaining caste based control. Expensive fruits and vegetables that were accessible to upper caste communities and which constituted a vegetarian diet were seen as 'pure' and meat eating as 'impure' and this 'impurity' then formed one of the largest pillars of justifying caste based discrimination and brutality.

Rajyashri then spoke about how this marginalization could be seen in cookbooks as well and how the cookbook is a site of power, where an upper caste and upper class food sensibility is normalized as the national food sensibility. A majority of recipes are the same five or six north Indian food dishes made in different ways, limiting the kind of food cultures that people engage with in India. In line with this Labbie Saniya reflected upon how certain recipes made in Muslim households can't be found on the internet or in cookbooks even if you go looking for them simply because of the invisiblisation and erasure of food histories and narratives of marginalized communities. One of the ways that this has been challenged, Saniya pointed out is through TikTok accounts of people like Shaik Afroze who made recipe videos of dishes that were not spoken of in popular discourse.

Further, Rajyashri then spoke about the transformative power of social media in this context where for lower caste people, seeing their community's food on these online platforms has enabled a sense of pride in their food cultures and reassured them about their backgrounds. This value of challenging traditional ways of representing food is what also made Rajyashri flip the idea of the cookbook on its head. She spoke about how the format of a cookbook is so particular. To begin with, it assumes literacy, that you can read and write, assumes you have access to a kitchen, utensils, and all the ingredients that you may need to cook someone else's food, try someone else's culture and step into their shoes in some ways. This led us to mulling over what that would mean when it comes to cooking Dalit cuisine. Do we think we can understand a marginalized community's experiences because we cook their food?

This was also one of the underlying reasons to why Rajyashri's impulse was to gravitate away from the tool of the discrimination itself, the cookbook. For her, looking at Dalit writers and literature and how much of it was about food urged her to chose and translate and compile these writings about food and the Dalit community's engagement with it instead of trying to mainstream Dalit food culture through a cookbook. And this challenge to pre-existing notions about art and literature and text is what continues to be remarkable about Rajyashri's work. She spoke about how it was a conscious decision to not aesthethise or 'beautify' her recipe compilations much. The words itself were the heroes of the compilations. And while her ceramic work has an aesthetic that she feels she has ownership over, she feels she is just a vessel for these recipes and poetry to pass through. Further, she spoke about these choices in her artistic practice and spoke about how she's very cognizant of challenging these boundaries as she navigates the art world. To keep being on the outside of the art scene, she believes would be another kind of exclusion albeit this time perhaps a self-inflicted one and spoke about how she was excited to see the ways in which art audiences and collectors engaged with her work and the forms the art took on later.

We concluded the session with some of the Fellows and alums reading the recipes out loud while Rajyashri left us with a very important thought to keep in my mind, that while the poems and stories she has compiled speaks about hunger and destitution, it is also important to look beyond the violence of it all and realise how these are also stories of everyday resistance and resilience of Dalit communities in the face of thousands of years of marginalization.