Kochi Biennale diaries

Team Culture Lab

6 February 2017

The Godrej India Culture Lab team spent a wonderful three days at the Kochi Biennale 2016. Three of us were experiencing it for the first time. Below is a little travelogue of our experience:

Dianne Tauro

I loved how the whole city of Fort Kochi is involved in the Biennale. Everyday buildings and warehouses and storerooms are converted into spaces of art. At the lab we try our best to be a non-intimidating space so our conversations are more accessible. When art becomes accessible, when the glass case around it is broken down, that’s when I resonate with art the most. I felt like the Biennale was attempting to do the same.

I particularly recall the Aspinwall House, the main venue of the biennale that I absolutely fell in love with. The nostalgic romance of its lost glory had me immediately. While moving from one hall to the next, ticking off each artist on the biennale map, we landed in a room that looked like an unused laboratory. The room was covered with small white tiles and had multiple platforms with cubicle like structures. This space housed Tokyo-based Yuko Mohri’s Calls. With magnets, rope, bells and a horn and many different kinds of magnets, her installation used magnetism to create different sounds. As I went around the room, I could not help but imagine what the original layout must have been at Aspinwall. Just as I would drift away in thought an old metal horn would create a sound that would draw me to the next contraption created by the artist.

At the Biennale, old buildings housed art, unused shops housed art, restaurants and gardens housed art and that brings me to The Pepper House. An art residency, cum hipster café, with a delightful library and a souvenir shop, The Pepper House hosted works in different mediums. Artist Javier Perez’s En Puntas (‘On Points’) has stayed with me. It features a ballerina performing on a piano with ballet shoes equipped with knives attached to them! The second was by Scottish artist Jonathan Owen who took an existing beautiful marble bust of a women and face carved out the statue’s face to replace it with a metal ball and chain. So powerful! They both spoke to me about the suffocating standards women hold themselves up to whether in beauty or whether in standards they place on themselves as they navigate the various roles they may play.

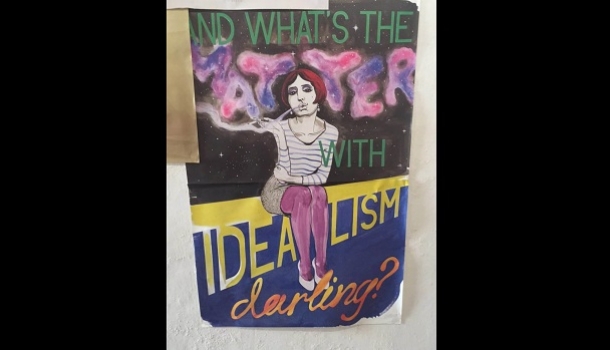

As I look back now at Kochi, there is one thing I always smile about. Charles Avery’s work - Untitled (What’s the Matter with Idealism, Darling?) at the Kashi Art Café summarises what I feel everybody should practice today… IDEALISM.

Saniya Shaikh

The more I engage with art, the more ways I discover of how it impacts us. The theme of Kochi-Muziris Biennale, ‘Forming In the Pupil of The Eye’ takes the viewer on a poetic journey of infinite possibilities and that is what distinguished the biennale from all the other art exhibitions I had previously attended. Despite the individual uniqueness of each of the many artworks, both in form and in idea, there was a synchronicity that created a flow of emotions – each feeding off the other, each responding to the other.

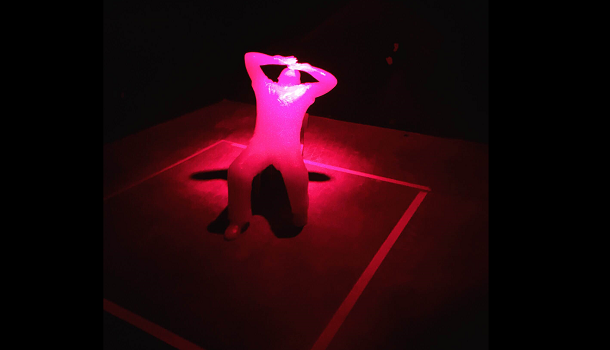

In a dingy room in the Aspinwall House sits a sculpture carved out of a single block of wax covering its eyes with its hand so as to shield it from the intense glare of the infrared light bulb placed right above its head. The art comes to life in the presence of a viewer, which causes the heat to intensify, threatening the existence of the sculpture. It thus comes down to a choice of determining one’s disappearance – at what point does one discard their curiosity in favour of the existence sculpture? The undertones of environmentalism with the analogy of melting glaciers and our destructive actions makes Multiple Choice a matter of serious inquisition of the relationship between oneself and the earth.

Alex Seton’s Refuge is a carrara marble sculpture that depicts a blanket draped around an absent figure. Ultra-realistic in appearance, the sculpture evokes fear and pain characteristic to displacement, catastrophe and isolation. Yet it is a home, a cloak of safety and warmth that acts as a barrier between oneself and the distress that one is surrounded with in the times of war. Impeccably carved and placed in an empty, old warehouse near the coast, the sculpture captures multiple realities of the crises around the world that need urgent attention.

The last piece of art that I would like to write about is one that I feel that I do not have any right to. I could not get myself to truly experience The Sea of Pain by Raúl Zurita. The work is an ode to Galip Kurdi, the brother of Alan Kurdi who, dressed in the lively tints of red and blue, was washed ashore after drowning from a perilous dinghy, trying to escape the brutal civil war in Syria with his family. The photo of his dead body made rounds on international media but there were no photographs of Galip. Zurita’s composition is placed at the end of a warehouse, filled knee-deep with sea water. Panels carrying the questions such as “Don’t you see me?”, “Don’t you feel me?” “/In the Sea of Pain”, overlook the viewer’s journey towards the poem and test their courage to digest the gruesomeness of the situation in Syria. Before I could even enter the warehouse, the intensity of the art consumed me. With my heart in my throat, I could not get myself to walk across the room and speak to Galip through Zurita’s words. It was the most difficult journey I have come across and I couldn’t even step in.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale experience for me was about disruption. It pushed me out of my mental fortress of comfort. It ended all the negotiations that I would have with myself to avoid questioning and challenging every action, every perception of mine. It pushed me to feel the things that I would choose not to, it shook me but it gave me the liberty to construct my own narratives.

Kevin Lobo

The last time I visited Kochi was when my father was based in there for nearly a year on one of his Air India job postings. The family had flown down to visit him during my college summer break. Being sheparded by parents from one landmark to the next – a church, the synagogue, a church, the backwaters, a church… my memory of Kochi was that it is a distinctly beautiful place that smelt of the sea and was definitely Catholic.

To say then that the visit to the same place a decade later with a bunch of radical cultural changemakers (our Culture Lab team) would be different is an understatement. It was an immersive three days that we spent in Kochi. Immersive in thought and immersive in art. The curation of the festival takes this forward. By the time we were done with section A of the Aspinwall House, I needed to take some time to breathe. The structure is breathtaking, build along the coast with its powdery white and blue walls, the years of decay of its outer shell peeks at you at regular intervals. The sea teases you as you walk through the rooms, showing up at unexpected times though the windows. But it was the art that made me want to take a minute to myself.

We went from art work to art work of Sudarshan Shetty’s seamlessly curated biennale which had seemingly disparate art works, in different mediums and in different voices, but screaming some form of dissent. After finishing the first section, I had my Kochi Biennale 2016 moment. I’d already read a lot on The Sea of Pain by Raúl Zurita, and was mentally ready, giddy with excitement to experience it. But it was the Pyramid of Exiled Poets by Aleš Šteger that got me. The title of the work is self-explanatory, audio pieces of poems being recited by exiled poets from different countries have been installed in the pyramid, but I was not ready for the experience. As you walk through the claustrophobia inducing, winding passages of the pyramid covered with cowdung cakes, you hear lines of poetry recited, in languages I had barely heard spoken, interloping with others voices.

With the walls closing in on me, the poems of a song that makes you uncomfortable filling my head, all I wanted to do was get out, but it never seemed to end. These lyrical treasures that I couldn’t understand struck a chord so deep that I welled up. I was glad to exit it, I was also really glad to have had a chance to experience it. Reflecting on the work a few days later, I realised it was the curation that got me. An experience that charged me emotionally that when I reached the pyramid, I had no choice but to surrender myself to what the art piece was making me feel.