Anand Grover on the 5 key milestones in the Section 377 battle

Team Culture Lab

4 February 2019

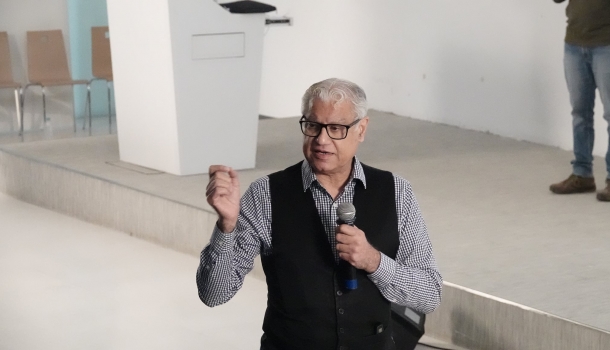

Anand Grover, senior advocate and director of Lawyers Collective, who argued on behalf of Naz Foundation from 2001 and Arif Jafar and Ashok Row Kavi in 2018, against section 377 speaks about the long journey to decriminalise homosexuality. Here are the key milestones that you need to know about.

September 6, 2018. History was created. A battle that had gone on for decades was finally won. Homosexuality was decriminalised by the Supreme Court when a five-judge Constitution Bench partially struck down provisions of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). It was a moment of sheer jubilation for the LGBTQ community.

Anand Grover, senior advocate and director of Lawyers Collective, had argued on behalf of Naz Foundation, the original petitioners against Section 377 and later on behalf of Arif Jafar and Ashok Row Kavi in 2018. He was one of the speakers at Queeristan - So Many Queer Indias, our spectacular event which explored the intersections that shape Indian queerness. He elaborated on five key milestones in the battle to decriminalise homosexuality:

1861: When it all began

Section 377 was modelled on England’s Buggery Act of 1533. It was introduced in 1861 by Thomas Macaulay, the first Chairman of the Law Commission of India who drafted the IPC. The section criminalised sexual activities that went “against the order of nature”. This broadly included homosexuality, anal penetration and bestiality.

“Section 377 is an alien imposition… a colonial law. In 19th century India, people who were transgender or gay were not discriminated against and were not criminals. In fact, they had an exalted status,” said Mr Grover.

2001: Taking the first step

The Lawyers Collective decided to challenge Section 377 after it realised that the law was being misused. “Many gay men told us that they were being blackmailed for money by people they went on dates with. We identified Section 377 as the source of evil for blackmail of gay men and the larger LGBTQI community,” said Grover.

The Naz Foundation, which worked with gay men, agreed to come onboard and file a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Delhi High Court.

2009: The first landmark decision

On July 2, 2009, the Delhi High Court legalised homosexual acts among consenting adults. This landmark judgement held Section 377 in violation of Articles 14 (Right to Equality), 15 (Prohibition of Discrimination) and 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty) of the Constitution.

“In a beautifully written judgement, Chief Justice AP Shah said that this law will not apply to men having consensual sex in private. They are free to do whatever they want in private. This is extremely important. What you do in your private sphere is your business and nobody, not even the government, can intrude in that space,” said Grover.

2013: A big blow

However, the jubilation after the 2009 judgement didn’t last long. “People who believed that what Section 377 said was our culture, woke up and rushed to the Supreme Court,” said Grover. What happened next turned out to be a setback: the apex court set aside the Delhi High Court’s decision and restored Section 377.

“11th December 2013 or 11-12-13 was an ominous day. Justice GS Singhvi said the decision of the Delhi High Court is wrong and questioned how a miniscule minority could claim fundamental rights. I wrote against the judgement because even one percent of society can invoke fundamental rights and succeed,” elaborated Grover.

2018: Freedom to love, at last

Five years later, history was finally made, as the five-judge bench, led by Dipak Misra, the Chief Justice of India, decriminalised consensual gay sex. The bench was hearing writ petitions filed in 2016 by award-winning Bharatanatyam dancer Navtej Singh Johar, and four others, including chef Ritu Dalmia and hoteliers Keshav Suri and Aman Nath.

“The Supreme Court said it is a constitutional morality. No marginalised group can be left out since it is an inclusive society. We are not living in a world where we can say that one group is not part of our culture. This is not tolerated by the court,” explained Grover.

The first stepping stone towards equality may have been achieved. However, according to the senior advocate, a lot more needs to be done. The next step? “Equality,” he says. “Equality principles do not apply in the private sector. The first thing that is required is an equality non-discrimination law that applies across the board to everybody.”

Justice Chandrachud also mentioned that the case involves much more than 'merely decriminalising certain conduct which has been proscribed by a colonial law'. The end of Section 377 could also be the beginning of other legal reforms for the LGBTQ community - marriage, adoption, property inheritance and guardianship rights. The 2018 judgement is just the beginning of a long road to the realisation of constitutional rights - but it is a historic stepping stone to the enjoyment of equal citizenship for the LGBTQ community.