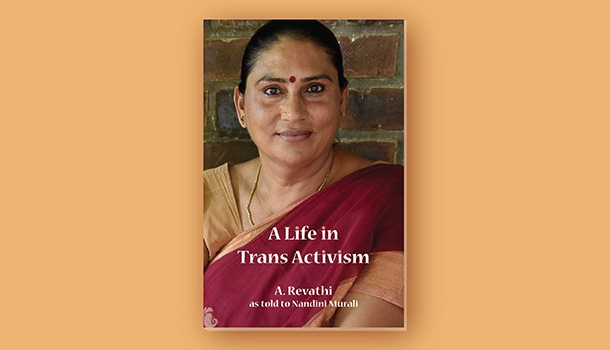

Book excerpt: A Life in Trans Activism

15 February 2019

In author A Revathi's book A Life in Trans Activism, she speaks of her childhood and her journey to becoming a spokesperson for transgender rights. She is also one of he panelists for our event So Many Feminisms! Here is an extract from the book:

Gradually, I began to find my calling as an activist who highlighted the needs, concerns and aspirations of the transgender community. It seemed the most natural thing to happen because I believe that there cannot be a better experience than the one born out of lived reality.

I did not become a trans woman on an impulse or because I was so arrogantly self-centered that I wished to disown every trace of my maleness. Rather, I became a trans woman because I had always felt that I was a woman. But a woman trapped in a male body. I wanted to free myself from this prison and embrace my femininity. That is the essence of my journey towards womanhood.

Writing emerged as the most powerful tool to showcase the lives of the hijras with sensitivity and compassion. Whatever affects the hijra community, also affects me personally. It was impossible for me to look the other way or keep quiet. Writing was the most effective tool to deal with the oppression. I had to write frankly and fearlessly about our lives that are lived perilously close to the edge.

There are several books written in English by people who have undergone sex change surgery abroad. But there were not many such books in Tamil, my first language. No other book, except the autobiography of Living Smile Vidya talked boldly about the lives of the hijras and the need to address the deadliness of the grave human rights violations we experience.

Meanwhile a deep personal crisis had a serious impact on me. I was disillusioned and wanted to quit my job at Sangama. I was also suicidal and wanted to end my life. My friends stood by me as pillars of strength and support.

They said to me, ‘Are you mad? You are doing such good work for the hijra community. So many changes have taken place. You too have grown in the process. Try not to muddle your thoughts. See if you can do something more for the community.’

I found their advice sensible. I decided to take my mind off the disturbing event in my life and do something constructive instead. This decision led me to undertake a study on the lives of the hijra community and put down our experiences in the form of a book.

I see my role as a writer to be another dimension of my work as a human rights activist. Writing, for me, is a powerful way to connect the hijra community, my family and society. Through bridging the huge gap between these two worlds, I hope to initiate a dialogue; to make people see the interconnections; to underscore the fact that as humans we have to fulfil our sense of individual and collective responsibility. Writing, like any other art form, allows us to bridge yawning chasms. Art is a great unifier and leveller. It cements relationships. It holds the key to long-closed doors that have become rusty due to centuries of prejudice and ignorance.

In 2003, I took a one-year break from work to work on my first book Unarvum Uruvamum (The Feelings and the Body). Written originally in Tamil, it captured the experiences of 25 hijras whom I personally interviewed, and traced their journeys from childhood to adulthood. Most of the hijras whose stories appear in the book lived in Tamil Nadu; a few of them lived in Bengaluru. I did not want to present the book in an academic style but wanted moving, deeply personalized stories that emerged during the course of intimate conversations between my people and me.

Initially they were surprised that I would want to write about them. Many of them were genuinely puzzled. They said to me, ‘Why do you want to write about us? What is the use?’

However, they were unanimous that I would be the best person to tell their stories for several reasons. According to them, only a hijra can truly understand hijras. They also believed that they could share their lives with me with openness and honesty that may not be possible for them with a person who was not a hijra. And lastly, they were certain that a hijra’s unique perspectives about the community would enable a lot of unknown facts about the community to emerge and also clear myths and misconceptions about the community. I was touched by their faith and trust in me. Yet they had several doubts that they wished to clarify with me.

‘Who is paying you? Will we get a share?’ they asked me.

I patiently answered every question. Finally I said to them, ‘Don’t we have to change the stigma and discriminations that still persist about our community? Shouldn’t we make people try to understand our emotions and feelings? This book is to make society understand that it is no fault of ours but a fault of society that we continue to lead such lives.’

I can never forget that moment. I saw joy and happiness on their faces. It was as if they had understood something that they had been struggling to understand all these years. It seemed as if a cloud had lifted from their view that had blocked the sunshine in their lives. From then on, each of the 25 people whose stories appear in the book shared their lives with me without any reservation. Even today when I recall how they wept while sharing their stories, my eyes fill with tears.

Until then, I thought that I was the only one to go through so much in life. But when I heard the stories of my community, many of them who had faced far more cruelty than me, all my suicidal tendencies vanished. It was a tonic that strengthened me and breathed new life into me.

(Extract courtesy Zubaan Books)